This article aims to answer the following questions about dreaming:

- What’s your approach to interpreting dreams?

- What do we know about dreaming?

- What are the benefits of dreaming?

- What is the best way to make a “dream journal” (coming in part 2)

What's your Approach to Interpreting Dreams?

Before enrolling at the faculty of Psychology at university, my attempts at interpreting my own dreams would always be met with mystery and woo-woo explanations. As a teenager, I committed the sin of purchasing a cheap dream interpretation book at a flea market. Despite some questionable aspects of the book – such as its guide of lottery numbers to play according to your dreams -- I would avidly turn to it to get some “answers” to my teenagerhood drama and existential doubt. I was feeling like an ancient Roman augur interpreting the will of the gods by observing the flight of the birds.

Augury is the practice in Ancient Rome of interpreting omens by observing the flight of the birds.

Only later on in my studies would I actually start approaching dreams in a more demystified and down-to-earth way as a means to get useful life insights, rather than expecting a one-size-fits-all answer. The turning point happened when one of my professor said the following sentence during a class:

“If a person asks you the meaning of his/her dream, start by asking what it means in his/her opinion.”

Not a big deal, right?

Nowadays, it still seems that the most common way to approach interpreting dreams is considering them as mysterious entities detached from the individual who experiences them. This view comes from a tradition consolidated in modern psychology with Freud and Jung, both stating that dreams come from the outside of an individual’s consciousness and have a hidden and implicit meaning covered by symbols. According to them, dreams are the symbolic narration of an unconscious reality. We know, in fact, that Freud would consider all dream appearances as symbolic distortions of unconscious sexual impulses (Freud, 1899).

Thankfully, today’s technological advancements have brought about progress in empirical research and the development of new theories on dreaming.

According to a recent article published in 2019 in the Sleep and Hypnosis Journal:

“Dreams are experiences just like waking experiences and a phenomenal self has its place in the center of these experiences as it has in the waking ones”.

Even though dreams might first appear to us as completely different, unclear or mysterious phenomena, they are just as much a part of our experiences as those from reality.

“In our opinion, one of the most important misconceptions of modern psychology is the idea that dreams cannot be explained without the concept of unconscious. It is a typical example of this delusion that Jung (1953) said that dreams would only be a ‘’ludus natura’’ (nature’s excrement) without the unconscious. However, dreams are our own experiences, just like our waking experiences.”

This implies that there is not necessarily a latent meaning to be deciphered, but that the dream can be read as a report of the current conflictual themes in the waking life of the dreamer.

This view is supported by one of the most common systems for conducting dream interpretations these days, called content analysis, which dissects the dream for statistical calculation, by counting how many elements of a certain category (like characters, social interactions, settings, emotions), appeared in the dream.

Through this approach researchers have found that dreams do not necessarily track our activities in waking life, but rather they track our concerns.

Dr. G. William Domhoff, a leading researcher in this field, said “dreams are dramatizations of our waking lives. Dreams emphasize how we feel about ourselves, the nature of our interactions, and our relationships.”

This implies that all of us have the ability to better understand ourselves and our lives through our own dreams.

Before you continue reading, you should stop for a second and ask yourself:

- What has been been your approach to interpreting dreams?

- Do you relate the content of the dream to your personal experiences or rather as separate, mysterious experiences?

What do we Know about Dreaming?

Today, there is a widespread understanding of dreams at a physiological level, YET the debate around why we dream has not yet reached consensus among the scholars.

In other words, we know that this succession of images, ideas, emotions, and sensations is present in all the stages of the sleep cycle (mainly in the rapid-eye movement, abbreviated REM). We also know that there are similarities between dreaming and waking states in our brain activity, but we don’t know much about their function.

The debate can be roughly divided into two camps:

- Researchers stating that dreaming might be just a product of physiological processes, for example, for getting rid of

superfluous information collected during our daily life.

According to this perspective, interpreting dreams is considered useless, because dreams themselves are not meaningful. One example of a theory taking this side is the “activation-synthesis hypothesis.”

Some scientific arguments state that dreams have any purpose at all beyond a purgative function to rid people of irrelevant information (Crick & Mitchison, 1983)

- many psychologists who practice dream therapy support the thesis that dreaming is not only purposeful, but it’s a wonderful opportunity to get insight and promote emotional healing.

Here we explore a big chunk of recent empirical research that supports the latter side of the debate

6 Science-supported Benefits of Dreams

- Dreams have an influence on emotional regulation in waking life. For example nightmares can have a positive effect

on coping (Picchioni & Hicks, 2009).

According to this cognitive psychological perspective, dreaming is like a psychological thermostat that allows us to evalsuate perceptions, regulate emotional arousal, and rehearse behavioral responses.

The book The Twenty-four Hour Mind: The Role of Sleep and Dreaming in Our Emotional Lives goes in depth into this perspective by analysing the murder of woman by her husband, who claimed to have no memory of the event. - Dreams seem to have a strong influence on creativity.

A large number of artists and scientists have reported being creatively stimulated by their dreams.

Novelist Stephen King turned a recurring childhood nightmare into the book "Salem's Lot."

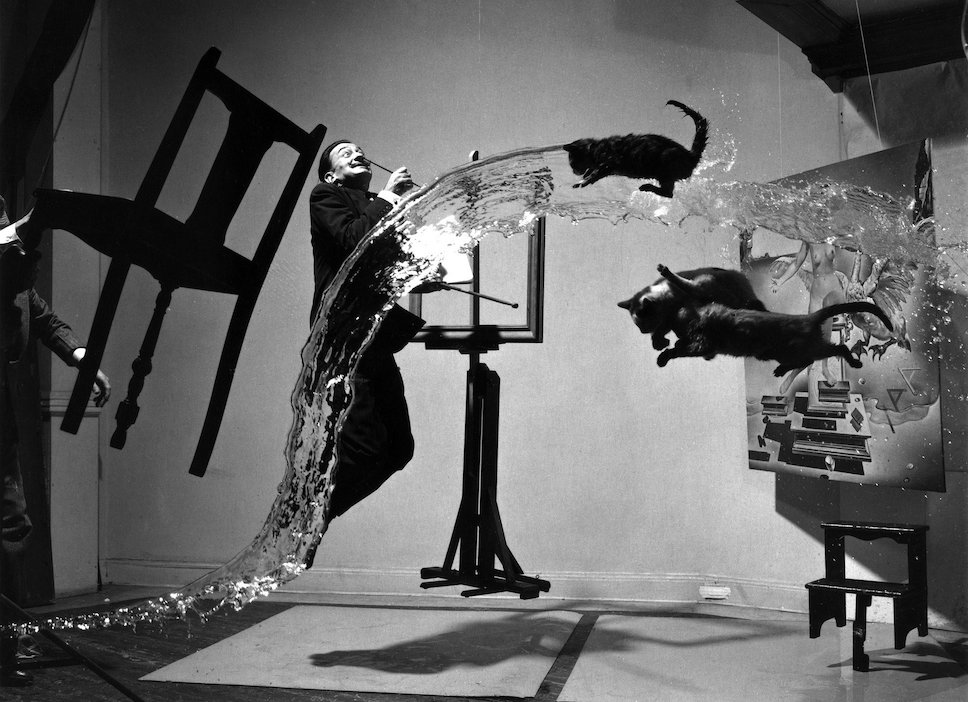

Salvador Dali was so obsessed with the creative potential of dreams that he deliberately fell asleep with a spoon in his hand. When he nodded off, the spoon would clatter to the ground and wake him up, providing fresh dream images for his surrealistic paintings.

Photograph: Salvador Dali

This branch of research suggests that dreams may help people from all walks of life find creative solutions to everyday problems. Dreams appear to boost at least one aspect of the creative process, such as the free association that precedes actual creation.

"To be creative, you need a way to let those circuits float free and really be open to alternatives that you would normally overlook," explains Robert Stickgold, PhD, an associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard University who has conducted seminal studies on dreams, sleeping and learning. "Several features of REM sleep predispose the brain to this activity." (from the “Dream canvas – Are dreams a muse to the creative?”) - Some research points out that dreaming plays a central role in the consolidation of memory content, and promotes insight, learning and

problem-solving.

In fact, memories constitute much of the source material for our dreams.

In particular, a research carried out by the University of Arizona highlighted that:- Sleep stages vary across the night: Early sleep is rich in NREM, but late sleep is rich in REM. These stage changes relate to, and are caused by, neurochemical fluctuations during sleep.

- Dream content varies as a function of sleep stage or time of night: there is considerable episodic content (information about where and when particular events occurred) in dreams during NREM/early sleep, but little episodic content in dreams during REM/late sleep.

- Sleep affects memory consolidation, but in a complex way: Procedural memory benefits from both REM/late sleep and NREM/early sleep, but episodic memory only benefits from NREM/early sleep.

Moreover, dream work has been utilized:

- As an alternative method of exploring one's feelings and cognitions about waking-life events (more about this in part 2 of this article).

- As indicators of physical or psychological stress. Researchers suggest

that particularly meaningful or charged experiences will be incorporated into the dreams of the night. That is, a variety of different types of presleep stimuli and in particular stressful stimuli find their way into dreams. This also depends from several factor, like the personality of the individual, the personal relevance of the stressor to the individual, and the nature and duration of the stressor.

Moreover, it has been suggested and demonstrated that a person must perceive a particular stimulus as a threat to his or her welfare for stress responses to occur.

- As a way to approach difficult topics such as death and dying or any other traumatic experience (although in such cases it might be relevant getting the support of a professional).

Convinced?

Grab a notebook and a pen and place it next to bedside, or simply download Journalisticapp and start writing down your dreams first thing in the morning in the apposite Dreams section.

Afterall, we know that the mobile-phone is the first thing we grab when we wake up...

Would you like to know how to Dream Journal?

Check out part 2 and subscribe below to get notified when we publish more articles related to journaling, productivity and mental health.

Resources:

Clara E. Hill, Roberta Diemer, Shirley Hess, Ann Hillyer, and Robyn Seeman Are the Effects of Dream Interpretation on Session Quality, Insight, and Emotions Due to the Dream Itself, to Projection, or to the Interpretation Process?

Christian Roesler Structural Dream Analysis: A narrative research method for investigating the meaning of dream series in analytical psychotherapies

Hayrettin Kara, Gökhan Özcan A new approach to dreams in psychotherapy: Phenomenological dream-self model

A Critical Literature Review of Dream Interpretation and Dream Work

Dream Content Analysis Explained by Nori Muster